Play with colors by combining plants

Plants are rich in colorants. In botanical dyeing, this richness makes it possible to broaden the palette of natural colors by playing with plants and successive baths.

What to do?

In two ways. There are certainly others. I’m talking about the ones I know.

Before getting started, two definitions are in order:

- The first bath: this is the bath with the highest concentration of colorant or organic mordant. This is the bath with which we dye for the first time.

- Depletion bath(es): the bath(es) with the least amount of colorant or organic mordant. This is the juice that remains after the first bath. It can be reused once, twice… or even more with certain plants that are very rich in coloring agents, such as campêche.

With botanical dyes, nothing is wasted. Vegetal nuances are enriched by the addition of different plants to the baths. Let me explain.

Composing plant colors with indigo

Indigo blue, a “foot” color

Indigo makes blue and nothing but blue. A more or less dark and intense blue, depending on the number of soaks and the amount of indigo in the vat.

But indigo opens the door to a much wider field of colors. Master dyers know this well. Many colors are made with indigo, thanks to an indigo “foot”. Indigo is used as the first dye, the first bath.

How do you make an indigo “foot”?

The fibers are dyed in a vat of indigo. The henna vat is the one I prefer and can be used on all types of fibre: wool, silk, linen, cotton… These fibers are then rinsed, washed and wrung out. They can be dried for later use, or used immediately for re-dyeing.

Composing new colors with indigo blue

Once indigo-dyed, the fibers can be immersed in a second dye bath. This is known as over-dyeing. If the mordanting stage is necessary for the plant in question, they are mordanted and then immersed in a dye bath.

Here are some suggestions for combining indigo with other plants:

Shades will vary according to the intensity of the blue and the amount of colorant in your plant bath used for over-dyeing:

- or it’s the first bath for strong colors,

- or a bath of exhaustion for more subtle nuances.

In short, these plant colors, known as compound colors, are made in several stages:

- Indigo dyeing,

- Rinse, wash, spin,

- botanical mordanting if necessary,

- Over-coating with another plant.

Shading plant colors

In botanical dyeing, colors are also shaded by successive baths of different plants.

Combine plants with similar affinities

In this case, it is important to associate plants that have the same needs to express color: bite, PH, water quality…

That’s why I’m proposing a partnership between :

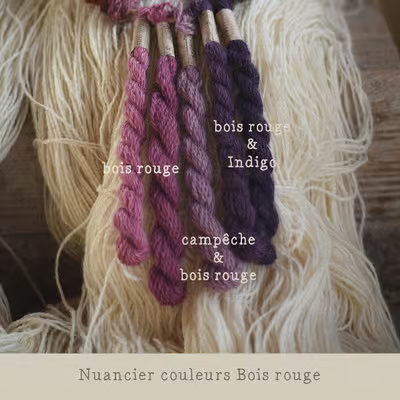

- bois rouge and campêche: for violets, purplish pinks and pinkish violets.

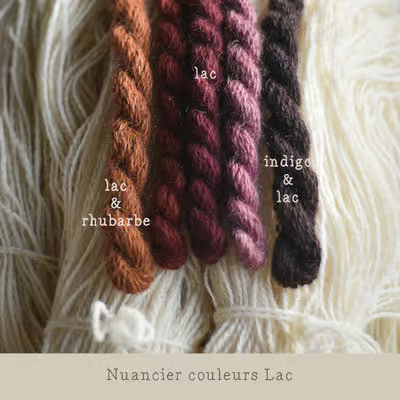

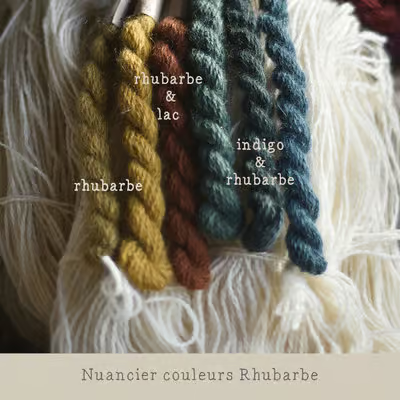

- lake and rhubarb: for oranges.

How do you go about it?

Take the example of rhubarb and the lake.

Dye in first rhubarb bath for a deep yellow (you can see the color obtained on embroidery threads – link in french). Keep the bath. It’s the bath of exhaustion.

Reuse the exhaust bath to dye new fibers (explanations are in the kit) for a lighter yellow.

Dye the fibers previously dyed with the rhubarb exhaustion bath in a first lac bath. For shades of orange.

We can also imagine two successive baths with the first bath of each plant or, conversely, with the exhaustion bath of each plant.

Take the time to play with nuances

Unlike indigo, it is not necessary to rinse or wash the fibers between the two botanical dye baths.

If you run out of time between baths, you can leave your fiber to dry for later use, and store your bath for some time in an airtight container. You can even freeze it. I hear it works well. I’m not in a position to confirm this. I don’t have a freezer.

The succession of baths is not the only factor in nuances

Shades will vary according to the quantity of colorants remaining in the baths, but also according to :

- water quality,

- bath cooking time,

- the type of fiber dyed (those shown in the photos are made with merino mohair wool),

- biting intensity: an exhausting bath of biting plant produces lighter colors,

- the mood of the dry cleaner!

This process allows you to use up all your baths while making botanical color. Once they’re all used up, you can compost them as long as you only use plants, as I do.

In your first experiments, I advise you not to look for a particular color, as you may be disappointed.

It’s more instructive and rewarding to multiply experiences by welcoming all the colors the plant has to offer.

This is my approach when I cook colors with plants.

Some nuances will disappoint you, others will excite you. By doing so, you’ll learn to play with colors. Write down every step you take, every experience you make, so you can do it again, even if the result is never completely identical. With a little experience, you’ll be able to make your own botanical dye color chart. The palette of natural colors to offer your wools and textiles becomes infinite.

Happy dyeing!